MEXICO CITY — Mexico’s former attorney general was arrested Friday in connection with the violent abduction and likely massacre of 43 students in 2014, a significant breakthrough in one of the most notorious atrocities in modern Mexican history.

He is the first high-level official to be detained in connection to the case, and the authorities said Friday that they had also issued more than 80 arrest warrants related to it, including for military officers, police officers and cartel members.

It was not immediately clear if any of those warrants had led to other arrests, but their sudden announcement came just a day after the Mexican government said an official inquiry had found the disappearance of the students to be a “crime of the state” involving every layer of government.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Tyler Mattiace, an Americas researcher at Human Rights Watch. “It shows a willingness and an interest in investigating and prosecuting not only the enforced disappearance of the students, but also the cover-up that happened afterward.”

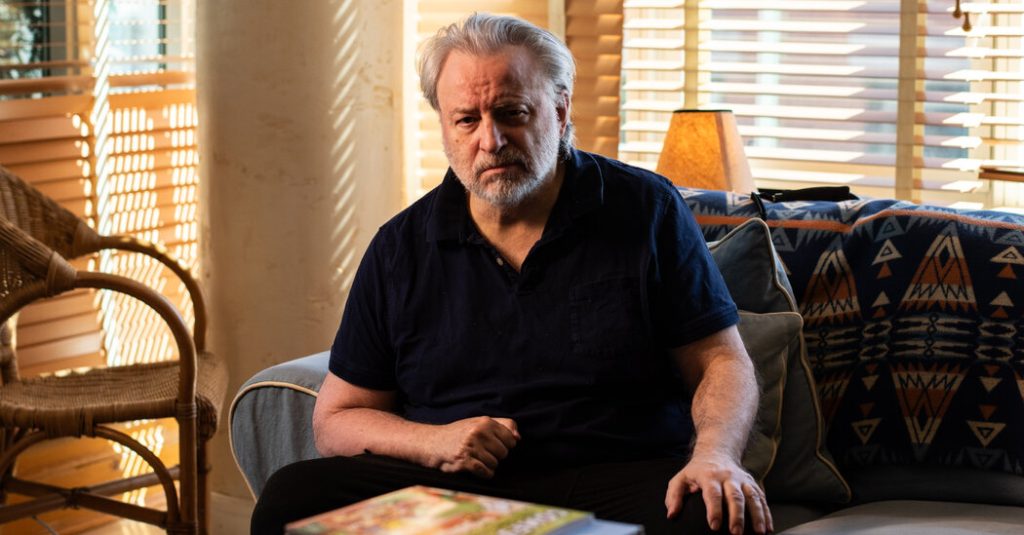

The arrest of the former attorney general, Jesús Murillo Karam, outside his home in Mexico City on Friday afternoon sent shock waves across the country. The Mexican prosecutor’s office said he was charged with “forced disappearance, torture and obstruction of justice” in the case of the students, young men from a teachers’ college in the rural town of Ayotzinapa.

Mr. Murillo oversaw a wide-ranging cover-up of the event, which included testimony obtained through torture, according to the United Nations. A report on the disappearances that Mr. Murillo released in January 2015, calling it the “historical truth,” has been widely discredited by independent experts, and the attorney general resigned shortly after amid criticism of his handling of the case.

His arrest is likely to be seen as a significant win for President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who rose to the presidency on a wave of discontent with the previous administration, vowing to tackle corruption and bring those responsible for the students’ disappearance to justice.

“We said from the start that we were going to tell the truth, no matter how painful it might be,” Mr. López Obrador said at a news conference on Friday. “Making the truth known has to do with transparency, which is a golden rule of democracy.”

Still, there is no guarantee the arrests will soon result in meaningful prosecution. The Mexican justice system often moves at a glacial pace, with detainees sometimes being held for years before being tried.

For all the scandals that plagued the previous government of President Enrique Peña Nieto, the current administration has obtained few convictions against former officials, including in a long-running graft investigation related to the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht. One of the top officials implicated in the case was extradited from Spain to Mexico in 2020, but only formally charged with bribery earlier this year.

“It’s a good sign, a powerful, clear, important gesture,” Paula Mónaco Felipe, a journalist and author of “Ayotzinapa: Eternal Hours,” said of Mr. Murillo’s arrest and the warrants. “However, it remains to be seen if they will be prosecuted.”

The families of the 43 students, who have spent years fighting for justice but have often been met with indifference or hostility by the authorities, reacted to the news cautiously.

In a statement issued through the Centro Prodh, a local advocacy group that represents them, they called the developments the beginning of a process that “could contribute to the accountability of the authorities involved.”

“The fathers and mothers are not moved by revenge or personal animosity against anyone,” the statement added, “but rather by the hope that the truth will be known and that this will help prevent similar events from ever happening again.”

Even in a country that had grown used to cartel-fueled carnage, the sudden disappearance of 43 students on a single night in September 2014 caused national outrage, with thousands taking to the streets in protest.

The night they disappeared, the students had commandeered several buses from a bus station in the town of Iguala, south of Mexico City, in order to transport their peers to a demonstration in the capital commemorating another student massacre from decades ago.

The practice of taking over buses was time-honored, and largely tolerated by local bus companies. But that night, they students were shot at and violently detained by police and local gunmen, before being taken away in separate groups and most likely murdered.

The government’s subsequent cover-up of events only added salt to the wound, particularly given ample evidence that local, state and federal agents had likely been involved in the students’ abduction. Rights groups have also long suspected the military was involved, but in Mexico the armed forces generally operate with impunity.

The Mexican army has been implicated in human rights abuses and forced disappearances for decades, going back to the 1970s when hundreds of student protesters and dissidents were arbitrarily detained, tortured and disappeared. But despite wide-ranging evidence, military commanders have almost never faced justice.

That made it particularly stunning that in an announcement this week of the preliminary findings of a government truth commission, the government said that the army had had an informant among the students and yet took “no action” to protect or find the young man.

He remains among the missing 43, and the inquiry said there is no indication that any of the young men are still alive. The news was also surprising given Mr. López Obrador’s increasing reliance on the military for everything from building airports to distributing vaccines.

The subsequent announcement that members of the military, including commanders, had been charged with crimes related to the disappearance of the students was another significant step, rights activists said.

“Let us hope that there is justice in the Ayotzinapa case, which is an emblematic case,” said Ms. Mónaco. The case “could open the door to truth and justice in many others, in at least 50 years of abuses and crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Mexican armed forces.”